The Hijacker

by Peter

United Airlines Flight 855 took off from Denver just before 5 pm on Friday, April 7, 1972. The plane had left from Newark, New Jersey earlier in the day, stopped in Denver to pick up more passengers, and was now on its way to Los Angeles with 85 passengers and 6 crewmembers. Twenty minutes into the flight a passenger was observed to be holding a hand grenade in his lap. The accounts of this are a little unclear, but it appears that he was observed by another passenger who informed a stewardess. The stewardess passed the information to the pilot.

|

| A United Airlines 727. Photo from Wikimedia Commons. |

The crew knew that an off-duty pilot was on the plane and asked him to casually examine the situation. As he approached the man's seat, the passenger drew a pistol. He then passed an envelope labelled, "Hijack Instructions" and demanded that the stewardess provide it to the captain. This had all transpired so quickly that most of the passengers were unaware that anything was amiss.

In the meantime, the pilot, after discussion with his crew, had announced that the plane was having mechanical trouble and would need to land in Grand Junction, Colorado. However, once the hijackers instructions were passed to him, the pilot opened the envelope and found a bullet, the pin of a grenade, and two pages of specific instructions requiring him to fly to San Francisco and park the plane in a specific location. The letter also detailed the number of people allowed near the plane on the ground, the distance at which all vehicles except fuel trucks were to be kept, and demanded $500,000 in cash (a little over $3 million in 2021), four parachutes, and the return of all written instructions.

After additional discussion, the crew decided to follow the instructions and announced that the plane needed to re-route to San Francisco for the supposedly required repairs.

Now, to understand the context of this story, I need to tell you a little bit about the status of air travel in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For those of us who have spent much of our lives in a post-9/11 travel environment, it can be shocking to learn about the sheer number of hijackings that took place in that time period. In fact, during the five years from 1968 to 1972, more than 130 planes were hijacked in the United States alone. That's an average of one hijacking every two weeks. In some cases, there were multiple hijackings on the same day. Although hijackers in the 1960s had mostly demanded free transportation to a desired location (Cuba was particularly popular), by the 1970s money (or other valuables like gold bars) was the preferred reward.

Security at airports was not set up to stop hijackers and it was the general policy of airlines to cooperate with them. After all, $500,000 is a lot cheaper than the lives of the passengers and crew, not to mention the plane. Most hijackings resulted in the safe release of the crew and passengers.

So, Flight 855, a Boeing 727, continued to San Francisco. Having been apprised of the situation, United Airlines officials decided to cooperate. They gathered the $500,000 and parachutes and had the plane refueled. After this was completed, the hijacker released the passengers and one stewardess. The hijacker had all of the crew move to the cockpit while he took a seat at the rear of the plane.

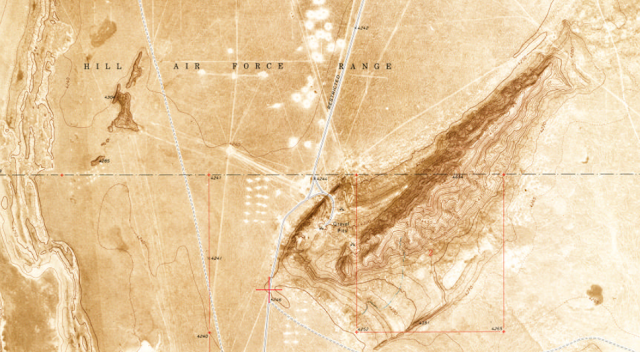

He then provided another set of instructions requiring the plane to follow a specific flight path at 16,000 feet and 200 miles per hour that would take it over several towns in Utah. The hijacker passed written notes back and forth to the captain, using the stewardess as a courier. He ordered the cabin depressurized and the cabin lights turned off. He said that if any pursuit planes were spotted, he would blow up the plane with a hidden explosive device. The hijacker blocked the peephole from the cockpit to the cabin, but was observed by the 2nd officer through a crack at the bottom of the door.

He changed into a jumpsuit and put on a helmet and parachute. He required updates on their speed and other relevant conditions. After the plane passed over the final community on the list (possibly Price), there were no more communications. The stewardess checked the cabin and found it empty. Six hours after the hijacking began (around 11:30 pm), the plane was able to turn to Salt Lake City.

One interesting note about the 727 is that it had a rear staircase (called the rear ventral airstair). This lowered out of the tail. Of particular note, this staircase had no mechanical locking mechanism and, because of its position, was not held closed by air pressure. It could be lowered while the airplane was in flight. This was the method used by Flight 855's hijacker, as well as the more famous D.B. Cooper, who also hijacked a 727.

|

| The rear ventral airstair on a 727. Photo by Piergiuliano Chesi via Wikimedia. |

The FBI in Salt Lake City sprang into action, combing the aircraft for clues. They recovered one handwritten note the hijacker had left behind, as well as materials such as the inflight magazine from his seat. In addition, they were aware that the hijacker had leapt from the plane in the general area of the Provo Airport. It is a little unclear how they knew this. It may have simply been the location of the plane at the time the hijacker stopped communicating. Some accounts also suggest that the parachutes provided by the airline had included an electronic tracker that was picked up by Air Force planes following the airliner.

Either that same night or the next day, a 14-year old Provo boy, exploring near the airport while his father changed a flat tire, found what he thought was a parachute pack in a culvert. He brought it to his father, who turned it in to the police when they returned to town. It was later found to be one of the four parachutes provided by United Airlines.

By 2 am on Saturday, April 8th, about 2-3 hours after the hijacker had bailed out, law enforcement officers from the FBI, Provo City Police Department, and Utah County Sherriff's posse combed the fields near the airport, walking at intervals of 20-30 yards. The search did not reveal the hijacker or any additional evidence.

However, as news of the hijacking spread that morning, tips began to come in. One, from a highway patrolman who was also in the Air National Guard stated that he and a friend had discussed hijackings a week or two previously and that the friend, Richard Floyd McCoy, Junior had said he had a foolproof plan for getting away with one. It had involved asking for parachutes from the airline, but using one you brought yourself so as not to be tracked.

|

| Richard Floyd McCoy, Junior |

McCoy was a 29-year old student at Brigham Young University (BYU) majoring in police science. He was married with two young children. The son of a career Army NCO from North Carolina, McCoy had also joined the Army out of high school, serving in various parts of the United States and in Germany. He also served two tours in Vietnam, one as a Green Beret (sometime given as more general "Special Forces") and one as a helicopter pilot. After returning home, he had attended BYU off and on over the course of around 7 years. By April 1972, he was close to finishing a busy semester (taking 21.5 credits) that would leave him with just 5.5 credits to complete during the summer. He also served in the Utah Air National Guard as a helicopter pilot, maintained a commercial helicopter pilot's license and was a competent skydiver who regularly skydived in Sandy. He is described as 5'10", 170 pounds with blue eyes and thinning dark brown hair.

Although one source suggests that McCoy was known to be in financial difficulties, others disagree. His wife worked full-time, including as a teacher at Provo High School the previous year, and had recently started a new job with the State of Utah. With the GI Bill covering his college expenses and his salary from the Air National Guard, the McCoy's were, if poor, not in dire straits. McCoy and his family were active in the Provo First Ward (local congregation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints), where he had recently been released from his position as a Sunday School Teacher.

FBI agents acting on the tip from the Utah Highway Patrolman (who is generally described as McCoy's best friend), interviewed McCoy, but did not arrest him. In the meantime, agents working to determine the hijacker's path from west Provo found a teenage employee at a hamburger stand who remembered selling McCoy a milkshake around 11:30 pm the night before and another teenager who had been paid $5 to drive McCoy back into town.

McCoy's sister-in-law, who was living with the family, apparently also reported to police that McCoy had asked for her assistance in an airline hijacking (the nature of this assistance was not explained that I could find). Agents examining the evidence from the airplane also recovered a partial print (from the in-flight magazine) matching McCoy's and determined that the handwritten note matched a sample of McCoy's handwriting from his Army days.

With this evidence in hand, McCoy was charged with aircraft piracy and interfering with flight crew. His home in Provo was surrounded and McCoy peacefully arrested. Agents later returned with a search warrant to search the home. Inside, they found $499,970, an army-style jumpsuit, helmet, and typewriters matching the typewritten notes.

McCoy was indicted by a grand jury on April 14, 1972 and convicted a few months later. He was sentenced to 45 years in prison. McCoy appealed his conviction, stating that the FBI had not had probable cause to search his home and the evidence from that search should be suppressed. The circuit court denied his appeal and the Supreme Court declined to take the case. At that point, in October 1973, McCoy faced a minimum of 15 years in prison before he stood any chance of release.

However, McCoy spent less than a year in the federal prison in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. Almost exactly two years after being sentenced, McCoy and three other prisoners commandeered a garbage truck (possibly armed with a pistol and knives) and crashed out through the gates. One newspaper account says that McCoy had also briefly escaped from prison in Denver, but I could find no corroboration of that account.

Two of the prisoners were recaptured shortly thereafter while robbing a nearby bank. However, McCoy and Melvin Walker, a bank robber from Missouri, eluded capture and were thought to have fled to McCoy's home state of North Carolina. Speculation in the press was the McCoy had hidden in a swamp near his hometown where he had spent time as a young man.

|

| McCoy's wanted poster after his escape from prison. |

Eventually, the FBI caught up with McCoy and Walker. They were staying in a house in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Agents, after identifying them, staked out the house for two days. When the escapees left the house, agents broke in and stationed themselves, awaiting their return. The car with the two fugitives returned, with Walker letting McCoy out while he circled the block again to observe the neighborhood. As McCoy entered the house, agents identified themselves and told him to stop. Instead, he drew a gun, firing one shot. An agent then shot him with a shotgun. Walker, hearing the shots, sped away, but was arrested shortly thereafter. Richard Floyd McCoy, Junior died of his wounds on November 10, 1974 at the age of 31.

Some authors, seeing the similarities in the modus operandi of McCoy and the infamous D.B. Cooper have suggested that they were one and the same. Other theories as to Cooper's true identity abound.

Comments

Post a Comment