Utah's School Bus Disaster

by Peter

On the morning of December 1, 1938, a school bus driven by 28-year old Ferrald Silcox would through the southern end of the Salt Lake Valley. Silcox was picking up students from Riverton, Bluffdale, South Jordan, and Crescent (now a part of Sandy, the area around 11000 South and State Street) for delivery to Jordan High School. A snowstorm had blanketed the southern end of the valley that morning and visibility and driving conditions were difficult.

Having picked up 38 students, Silcox took the bus north on 300 West, which ran adjacent to the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad mainline into Salt Lake City. Silcox ran a tight ship on his bus and the students were talking quietly. At about 10200 South, only a few blocks from the High School, the road took a 90-degree turn across the tracks, called Burgon's Crossing, before continuing north. Just before 9 am, the bus paused at the crossing and then, to the horror of onlookers, proceeded onto the tracks directly into the path of the 85-car 'Flying Ute' fast freight.

The Flying Ute was the D&RGW's second class freight, carrying loads from Pueblo, Colorado to Salt Lake City at the same speed as a passenger train. It too had been delayed by the snow through Helper and Soldier Summit, reaching Provo four hours late. Led by a 314-ton Challenger locomotive, the train was part of a new generation of fast steam trains capable of speeds of up to 70 miles per hour.

Approaching Burgon's crossing, the train was traveling just over 50 miles per hour. As required to by law, the train crew, who saw the school bus parallel to, and ahead of them, blew their horn for around 1,500 feet (approximately 20 seconds) before reaching the crossing.

The bus Silcox was driving was unheated, except for a defroster for the front windshield. With the cold weather, the windows were closed and covered in condensation. Pausing at the crossing, the driver could neither see nor hear the oncoming train.

As the bus moved forward, the fireman on the locomotive called a warning to the engineman. The engineman hit the emergency brakes, but a train that size takes nearly a half mile to stop. Most of the body of the bus was thrown 100 feet from the tracks, while the steel chassis was wrapped around the front of the locomotive and dragged for the half mile, scattering band instruments, school papers, and the bodies of students along the way.

First responders gathered as many ambulances as could be found to take the injured, dying, and dead to Salt Lake General Hospital at 2100 South State Street. Parents gathered at the site, checking the bodies as they were loaded to try to find their children. The ambulances with living patients raced at 70 miles per hour to the hospital, while those carrying the dead traveled without lights or sirens, passing students waiting to be taken home from Jordan High, where classes had been canceled in light of the tragedy.

Of the passengers on the bus, 23 students and the driver were killed, or died of the wounds in the enxt few days. The other 15 lived, although 7 had been seriously injured and many bore the effects of their injuries through their entire lives.

In the aftermath of the accident, the Interstate Commerce Commission, who oversaw the operations of railroads, investigated. They determined that Silcox had not been able to see or hear the oncoming train. They recommended that school buses be required not only to stop at railroad crossings, but also to open their doors. This would allow them to both see and hear oncoming trains, unobstructed by foggy windows or noisy students. Over the next few years, spurred by this and other, similar tragedies, every state adopted the recommendation.

The Jordan High crash is neither the worst train crossing accident in US history (the 1963 Chualar crash in Salinas, California killed 32 migrant workers and injured 25), nor the worst school bus accident (there have been a number with more fatalities). However, it was important because of the youth of its victims and the changes to security procedures it spurred. It also provides a good model for responding to tragedy, from the response of police and fire personnel, the gathering of the communities around the families of the victims, investigation by proper authorities, and recommendation and adoption of measures to reduce the risk of reoccurrence.

For other interesting items in the area, see my posts on the Salt Lake Army Air Force Jeep Ranges, Phantom Wye, the Longest Conveyor Belt in the World, and the WWI Internment Camp at Fort Douglas.

Hotels in South Jordan can be found here.

On the morning of December 1, 1938, a school bus driven by 28-year old Ferrald Silcox would through the southern end of the Salt Lake Valley. Silcox was picking up students from Riverton, Bluffdale, South Jordan, and Crescent (now a part of Sandy, the area around 11000 South and State Street) for delivery to Jordan High School. A snowstorm had blanketed the southern end of the valley that morning and visibility and driving conditions were difficult.

Having picked up 38 students, Silcox took the bus north on 300 West, which ran adjacent to the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad mainline into Salt Lake City. Silcox ran a tight ship on his bus and the students were talking quietly. At about 10200 South, only a few blocks from the High School, the road took a 90-degree turn across the tracks, called Burgon's Crossing, before continuing north. Just before 9 am, the bus paused at the crossing and then, to the horror of onlookers, proceeded onto the tracks directly into the path of the 85-car 'Flying Ute' fast freight.

The Flying Ute was the D&RGW's second class freight, carrying loads from Pueblo, Colorado to Salt Lake City at the same speed as a passenger train. It too had been delayed by the snow through Helper and Soldier Summit, reaching Provo four hours late. Led by a 314-ton Challenger locomotive, the train was part of a new generation of fast steam trains capable of speeds of up to 70 miles per hour.

|

| A Challenger locomotive from the Union Pacific. By Mark Evans - originally posted to Flickr as Challenger 01, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7581984 |

Approaching Burgon's crossing, the train was traveling just over 50 miles per hour. As required to by law, the train crew, who saw the school bus parallel to, and ahead of them, blew their horn for around 1,500 feet (approximately 20 seconds) before reaching the crossing.

The bus Silcox was driving was unheated, except for a defroster for the front windshield. With the cold weather, the windows were closed and covered in condensation. Pausing at the crossing, the driver could neither see nor hear the oncoming train.

As the bus moved forward, the fireman on the locomotive called a warning to the engineman. The engineman hit the emergency brakes, but a train that size takes nearly a half mile to stop. Most of the body of the bus was thrown 100 feet from the tracks, while the steel chassis was wrapped around the front of the locomotive and dragged for the half mile, scattering band instruments, school papers, and the bodies of students along the way.

|

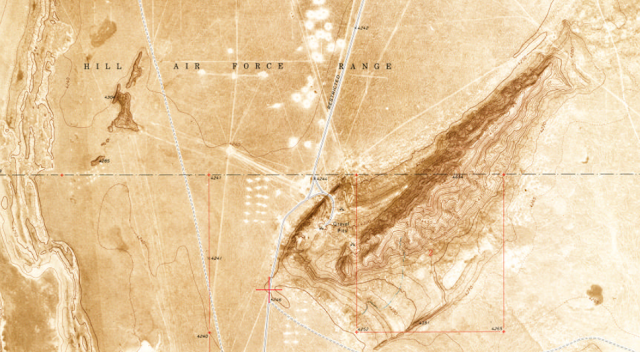

| A map of the site of the accident. The aerial photograph is from 1937, the year before the accident. |

First responders gathered as many ambulances as could be found to take the injured, dying, and dead to Salt Lake General Hospital at 2100 South State Street. Parents gathered at the site, checking the bodies as they were loaded to try to find their children. The ambulances with living patients raced at 70 miles per hour to the hospital, while those carrying the dead traveled without lights or sirens, passing students waiting to be taken home from Jordan High, where classes had been canceled in light of the tragedy.

Of the passengers on the bus, 23 students and the driver were killed, or died of the wounds in the enxt few days. The other 15 lived, although 7 had been seriously injured and many bore the effects of their injuries through their entire lives.

|

| The Denver and Rio Grande mainline today, at about 7300 South. |

In the aftermath of the accident, the Interstate Commerce Commission, who oversaw the operations of railroads, investigated. They determined that Silcox had not been able to see or hear the oncoming train. They recommended that school buses be required not only to stop at railroad crossings, but also to open their doors. This would allow them to both see and hear oncoming trains, unobstructed by foggy windows or noisy students. Over the next few years, spurred by this and other, similar tragedies, every state adopted the recommendation.

The Jordan High crash is neither the worst train crossing accident in US history (the 1963 Chualar crash in Salinas, California killed 32 migrant workers and injured 25), nor the worst school bus accident (there have been a number with more fatalities). However, it was important because of the youth of its victims and the changes to security procedures it spurred. It also provides a good model for responding to tragedy, from the response of police and fire personnel, the gathering of the communities around the families of the victims, investigation by proper authorities, and recommendation and adoption of measures to reduce the risk of reoccurrence.

For other interesting items in the area, see my posts on the Salt Lake Army Air Force Jeep Ranges, Phantom Wye, the Longest Conveyor Belt in the World, and the WWI Internment Camp at Fort Douglas.

Hotels in South Jordan can be found here.

Comments

Post a Comment